Seven Days in May

| Seven Days in May | |

|---|---|

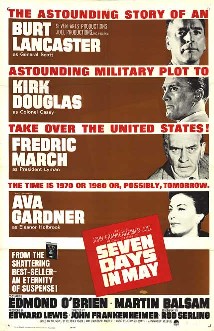

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Frankenheimer |

| Screenplay by | Rod Serling |

| Based on | the novel by Fletcher Knebel & Charles W. Bailey II |

| Produced by | Edward Lewis |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ellsworth Fredricks A.S.C. |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.2 million |

| Box office | $3,650,000 (rentals)[1] |

Seven Days in May is a 1964 American political thriller film about a military-political cabal's planned takeover of the United States government in reaction to the president's negotiation of a disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. The film, starring Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Fredric March, and Ava Gardner, was directed by John Frankenheimer from a screenplay written by Rod Serling and based on the novel of the same name by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II, published in September 1962.[2]

Plot

[edit]During the Cold War, the unpopular U.S. President Jordan Lyman has signed a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union, and ratification by the Senate produced a wave of dissatisfaction, especially among Lyman's political opposition and the military, who believe the Russians cannot be trusted. His popularity reaches an all-time low of 29%, and rioting about the treaty occurs right outside the White House. The presidential physician warns him of a dangerous cardiac condition which he blithely disregards, too busy to take a prescribed two-week vacation.

United States Marine Corps Colonel "Jiggs" Casey is the Director of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He serves its chairman, four-star United States Air Force general James Mattoon Scott, a highly-decorated commander and air ace.

Casey stumbles upon evidence that Scott is leading the Joint Chiefs to stage a coup d'etat to remove Lyman in seven days. Under the plan, disguised as a training exercise, a secret army unit known as ECOMCON, training at a secret Texas base, will take control of the country's telephone, radio, and television networks while the president, participating in a staged "alert," is seized. Scott, who is busy advancing his charismatic public persona through nationally televised anti-treaty rallies, plans to head a military junta. Although personally opposed to Lyman's policies, Casey is appalled by the plot and alerts Lyman.

Still somewhat skeptical, Lyman gathers a circle of trusted advisors to investigate: Secret Service White House detail chief Art Corwin, Treasury Secretary Christopher Todd, longtime advisor Paul Girard, and Raymond Clark, the senior U.S. senator from Georgia and a close friend of 21 years.

Casey has deduced that the heads of all U.S. military branches but the Navy support Scott's coup scheme, with Vice Admiral Barnswell, then aboard an aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean, apparently the only invited officer to decline. Lyman cancels a previous commitment to participate in Scott's alert, pretending he will be away for a fishing weekend. He then dispatches Girard to Gibraltar to obtain Barnswell's confession, sends the alcoholic Clark to Texas to locate the secret base, and tasks Casey to gather dirt on the general's private life. Meanwhile, the Secret Service surreptitiously films evidence of an attempt to kidnap the president during the phony fishing trip, removing all doubts about the existence of a plot.

Girard successfully secures Barnswell's confession in writing, but this is lost with him when a plane crash in Spain claims his life. Clark is taken captive when he reaches the secret base and held incommunicado. Exploiting Casey's longtime friendship with the base's deputy commander Colonel Henderson, Clark convinces Henderson of the actual intent of the impending "alert". Henderson frees Clark and leads an escape back to Washington but is abducted and confined in a military stockade. In a radiophone conference call with the president, Barnswell denies knowledge of any conspiracy.

Knowing he cannot prove Scott's guilt, Lyman nevertheless calls Scott to the White House to demand that he and the other conspirators resign. Scott refuses and denies the existence of any plot. Lyman argues that a coup would prompt the Soviets to launch a preemptive nuclear strike. Scott maintains that the American people are behind him. Lyman challenges him to resign and run for office in order to seek power legitimately, but Scott is unmoved. Lyman restrains himself from confronting Scott with damning letters that Casey had obtained from Scott's former mistress Eleanor Holbrook. Casey, who has his own romantic interest in Holbrook, eventually returns them to her.

Scott meets the other three Joint Chiefs and reasserts his intention to execute the coup. He plans a nighttime network broadcast, but Lyman holds an afternoon press conference to announce he has fired the four men. As he speaks, Barnswell's confession, recovered from the plane crash, is handed to him and he delays the conference. In the interim, copies of the confession are delivered to Scott and the other plotters. As the conference resumes, Scott abandons the plan and, devastated, returns home when Lyman announces that the other three conspirators have resigned.

Lyman delivers a speech on the state of the nation and its values, declaring that the nation gains strength through peace rather than by conflict. The press corps applauds.

Cast

[edit]

|

|

Uncredited speaking roles (in order of appearance)

[edit]- Malcolm Atterbury, as Horace, the president's physician: "Why, in God's name, do we elect a man president and then try to see how fast we can kill him?"

- Jack Mullaney, as LTJG Grayson: "All properly decoded in four point oh fashion and respectfully submitted by yours truly, Lieutenant junior grade Dorsey Grayson."

- Charles Watts, as Stu Dillard, Washington insider: "Oh, Senator, pardon me, come along, I want you to meet the wife of the Indian ambassador."

- John Larkin, as Colonel John Broderick, one of the conspirators: "Well, well, well, if it isn't my favorite jarhead himself, Jiggs Casey."

- Colette Jackson, as the woman speaking to Senator Clark in Charlie's Bar, near secret base in Texas: "You wonder what the country's comin' to. All those boys sittin' up in the desert never seein' no girls. Why, they might as well be in stir."

- John Houseman, as Vice Admiral Farley C. Barnswell, defaulted conspirator: "I'm sorry, sir. I can only recount to you the situation as it occurred. I signed no paper. He took nothing with him."

- Rodolfo Hoyos Jr., as Captain Ortega, in charge of the airplane crash site in Spain: "There were only two American nationals on board—a Mrs. Agnes Buchanan from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and a Mister Paul Girard. His destination was Washington."

- Fredd Wayne, as Henry Whitney, official from the American embassy in Spain: "You find any effects of the Americans? Anything at all?"

- Tyler McVey, as General Hardesty, NORAD commander: "Barney Rutkowski, Air Defense. He's screaming bloody murder about those twelve troop carriers dispatched to El Paso."

- Ferris Webster (editor of the film), as General Barney Rutkowski: "There's some kind of a secret base out there, Mr. President, and I think I should have been notified of it."[3]

Background

[edit]The book was written in late 1961 and into early 1962 during the first year of the Kennedy administration, reflecting some of the events of that era. In November 1961, President John F. Kennedy accepted the resignation of vociferously anti-communist general Edwin Walker, who had been indoctrinating the troops under his command with radical right-wing ideas and personal political opinions, including describing Harry S. Truman, Dean Acheson, Eleanor Roosevelt, and other active public figures as communist sympathizers.[4] Although no longer in uniform, Walker continued to make headlines as he ran for governor of Texas and made speeches promoting strongly right-wing views. In the film version of Seven Days in May, Fredric March, portraying the narrative's fictional president Jordan Lyman, mentions General Walker as one of the "false prophets" who were offering themselves to the public as leaders.

As Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey II, primarily political journalists and columnists, collaborated on the novel, they also conducted interviews with another highly controversial military commander, the newly appointed Air Force chief of staff General Curtis LeMay, who was angry with Kennedy for refusing to provide air support for the Cuban rebels in the Bay of Pigs Invasion.[5][6] The character of General James Mattoon Scott was believed to have been inspired by both LeMay and Walker.[7]

President Kennedy had read the novel Seven Days in May shortly after its publication and believed that the scenario could actually occur in the United States. According to director John Frankenheimer, the project received encouragement and assistance from Kennedy through White House press secretary Pierre Salinger, who conveyed to Frankenheimer Kennedy's wish that the film be produced. In spite of Defense Department opposition, Kennedy arranged to visit the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis Port for a weekend when the film needed to shoot outside the White House.[8]

Production

[edit]Kirk Douglas and director John Frankenheimer were the moving forces behind the filming of Seven Days in May; the film was produced by Edward Lewis through Douglas's company Joel Productions and Seven Arts Productions. Frankenheimer recruited screenwriter Rod Serling. Douglas intended to star in the film along with his frequent costar Burt Lancaster. Douglas offered Lancaster the General Scott role, while Douglas agreed to play Scott's assistant.[9] Frankenheimer commissioned Nedrick Young to rewrite the scene in which Casey visits Holbrook at her apartment.[10]: 1:05:00

Lancaster's involvement nearly caused Frankenheimer to withdraw from the project, as the two men had conflicted during the production of Birdman of Alcatraz two years earlier. Only Douglas's assurances that Lancaster would behave kept Frankenheimer on the project.[11] Lancaster and Frankenheimer were at peace during the filming, but Douglas and Frankenheimer sparred with one another.[12][13] Frankenheimer was very happy with Lancaster's performance, especially the long scene toward the end between Lancaster and March, saying that Lancaster was "perfect" in his delivery.[10] Frankenheimer stated decades later that he considered Seven Days in May among his most satisfying work.[10] He saw the film as putting "a nail in the coffin of McCarthy."[10]: 1:36:00

The filming took 51 days and according to the director the production was a happy affair, with all of the actors and crew displaying great reverence for Fredric March.[10] Many of Lancaster's scenes were shot at a later time as he was recovering from hepatitis.[10] Ava Gardner, whose scenes were shot in just six days, thought that Frankenheimer favored the other actors over her. Frankenheimer remarked that she was sometimes "difficult."[10]: 1:06:00 Martin Balsam objected to Frankenheimer's habit of shooting pistols behind him during important scenes.[11] Frankenheimer had been briefly stationed in the mailroom at the Pentagon early in his Korean war service and stated that the sets were totally authentic, praising the production designer.[10] Further providing authenticity, many of the scenes in the film were loosely based on real-life events of the Cold War.[14]

In an early example of guerrilla filmmaking, Frankenheimer photographed Balsam ferrying to the supercarrier USS Kitty Hawk in San Diego without prior permission. Another example occurred when Frankenheimer wanted a shot of Douglas entering the Pentagon, but unable to receive permission, he rigged a camera in a parked car.[15]

Frankenheimer recruited well-known producer and friend John Houseman to play Vice Admiral Farley C. Barnswell in his uncredited acting debut. Houseman agreed in return for a fine bottle of wine (seen during the telephone scene).[10]: 1:30:00 Several scenes, including one with standins for nuns, were shot inside the recently built Washington Dulles International Airport, and the production team was the first to ever film there.[10] The alley and car-park scene was shot in Hollywood, and other footage was shot in the Californian desert in 110-degree heat. The secret base and airstrip were specially built in the desert near Indio, California, and an aircraft tail was used in one shot to create the illusion of a whole plane off screen.[10] The original script had Lancaster dying in a car crash at the end after hitting a bus, but this was dropped in favor of a scene showing him leaving for home in his limousine, a scene that was shot in Paris during production of The Train (1964).[10]

Presidential press secretary Pierre Salinger conveyed to Frankenheimer that President Kennedy had read the book and hoped that the film would be produced. Kennedy arranged a visit to the family compound in Hyannis Port one weekend so that the riot scene could be filmed outside the White House.[16][17]

Frankenheimer considered the scene in which Douglas's character visits the president to be a masterful bit of acting which would have been very difficult for most actors to sustain.[10] He had done similar scenes on many television shows, and not only the acting but also every camera angle and shot were extensively planned and rehearsed. Frankenheimer paid particular attention to ensuring that all three actors in the scene were in focus for dramatic impact. Many of Frankenheimer's signature techniques were used in scenes such as this throughout the film, including his "depth of focus" shot with one or two people near the camera and another or others in the distance and the "low angle, wide-angle lens" (set at f/11) which he considered to give "tremendous impact" on a scene.[10]

The film is set several years in the future from the time of its release. Although "1970" appears on a Pentagon display and the registration sticker on the rear license plate of Senator Prentice's Bentley sedan, the day/date indicator in the Pentagon depicts TUES / MAY 13, a date occurring only in such post-1964 years as 1969, 1975, 1980 or 1986. Other nods include a situation room which was designed to seem futuristic, as well as the utilization of then-futuristic technology of video teleconferencing and the recently issued and exotic-looking M16 rifle. Additionally, the concept of a nuclear treaty between Cold War powers anticipated the actual existence of one.[10]: 1:45:00

Soundtrack

[edit]David Amram, who had previously scored Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962), originally provided music for the film, but Lewis was unsatisfied with his work. Jerry Goldsmith, who had worked with the producer and Douglas on Lonely Are the Brave (also 1962) and The List of Adrian Messenger (1963), was signed to rescore the project.

Goldsmith composed a very brief score (lasting around 15 minutes) using only pianos and percussion; he later scored Seconds (1966) and The Challenge (1982) for Frankenheimer.[18]

In 2013, Intrada Records released Goldsmith's music for the film on a limited-edition CD (paired with Maurice Jarre's score for The Mackintosh Man – although that film was produced by Warner Bros. while Seven Days in May was theatrically released by Paramount. The entire Seven Arts Productions library had been acquired by Warner Bros. back in 1967.

Reception

[edit]Seven Days in May premiered on February 12, 1964 in Washington, D.C.,[19] to good critical notices and audience response.[11]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The film was nominated for two 1965 Academy Awards,[20] for Edmond O'Brien for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration/Black-and-White for Cary Odell and Edward G. Boyle. In that year's Golden Globe Awards, O'Brien won for Best Supporting Actor, and Fredric March, John Frankenheimer, and composer Jerry Goldsmith received nominations.

Frankenheimer won a Danish Bodil Award for directing the Best Non-European Film, and Rod Serling was nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Written American Drama.

Evaluation in film guides

[edit]Steven H. Scheuer's Movies on TV (1972–73 edition) gives Seven Days in May its highest rating of four stars, recommending it as "an exciting suspense drama concerned with politics and the problems of sanity and survival in a nuclear age", with the concluding sentences stating, "benefits from taut screenplay by Rod Serling and the direction of John Frankenheimer, which artfully builds interest leading to the finale. March is a standout in a uniformly fine cast. So many American-made films dealing with political subjects are so naive and simple-minded that the thoughtful and, in this case, the optimistic statement of the film is a welcome surprise." By the 1986–87 edition, Scheuer's rating was lowered to 3½ and the conclusion shortened to, "which artfully builds to the finale", with the final sentences deleted. Leonard Maltin's TV Movies & Video Guide (1989 edition) gives it a still lower 3 stars (out of 4), originally describing it as an "absorbing story of military scheme to overthrow the government", with later editions (including 2014) adding one word, "absorbing, believable story..."

Videohound's Golden Movie Retriever follows Scheuer's later example, with 3½ bones (out of 4), calling it a "topical but still gripping Cold War nuclear-peril thriller" and, in the end, "highly suspenseful, with a breathtaking climax." Mick Martin's & Marsha Porter's DVD & Video Guide also puts its rating high, at 4 stars (out of 5) finding it, as Videohound did, "a highly suspenseful account of an attempted military takeover..." and indicating that "the movie's tension snowballs toward a thrilling conclusion. This is one of those rare films that treat their audiences with respect." Assigning the equally high rating of 4 stars (out of 5), The Motion Picture Guide begins its description with "a taut, gripping, and suspenseful political thriller which sports superb performances from the entire cast", goes to state, in the middle, that "proceeding to unravel its complicated plot at a rapid clip, SEVEN DAYS IN MAY is a surprisingly exciting film that also packs a grim warning", and ends with "Lancaster underplays the part of the slightly crazed general and makes him seem quite rational and persuasive. It is a frightening performance. Douglas is also quite good as the loyal aide who uncovers the fantastic plot that could destroy the entire country. March, Balsam, O'Brien, Bissell, and Houseman all turn in topnotch performances and it is through their conviction that the viewer becomes engrossed in this outlandish tale."

British references also show high regard for the film, with TimeOut Film Guide's founding editor Tom Milne indicating that "conspiracy movies may have become more darkly complex in these post-Watergate days of Pakula and paranoia, but Frankenheimer's fascination with gadgetry (in his compositions, the ubiquitous helicopters, TV screens, hidden cameras and electronic devices literally edge the human characters into insignificance) is used to create a striking visual metaphor for control by the military machine. Highly enjoyable." In his Film Guide, Leslie Halliwell provided 3 stars (out of 4), describing it as an "absorbing political mystery drama marred only by the unnecessary introduction of a female character. Stimulating entertainment." David Shipman in his 1984 The Good Film and Video Guide gives 2 (out of 4) stars, noting that it is "a tense political thriller whose plot is plotting".

Remake

[edit]The film was remade in 1994 by HBO as The Enemy Within with Sam Waterston as President William Foster, Jason Robards as General R. Pendleton Lloyd, and Forest Whitaker as Colonel MacKenzie "Mac" Casey. This version followed many parts of the original plot closely, while updating it for the post–Cold War world, omitting certain incidents and changing the ending.

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 1964

- Politics in fiction

- Dr. Strangelove, another 1964 film about a rogue general in the Cold War dealing with the nuclear arsenal

- A Very British Coup, a 1988 three-episode serial, based on Chris Mullin's novel about an attempted right-wing overthrow of a left-wing British government

References

[edit]- ^ "Big Rental Pictures of 1964", Variety, p. 39, January 6, 1965.

- ^ "Seven Days in May" (Kirkus Reviews, September 10, 1962)

- ^ Seven Days in May cast list at American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ "Armed Forces: I Must Be Free..." (Time Magazine, November 10, 1961)

- ^ Stoddard, Brooke C. "Seven Days in May: Remembrance of Books Past" (Washington Independent Review of Books, November 27, 2012)

- ^ Steed, Mark S. "Seven Days in May by Knebel and Bailey - Book Review" (An Independent Head, October 26, 2013)

- ^ Quart, Leonard. "Seven Days in May (Web Exclusive)". Cineaste. XLII (4). Retrieved December 26, 2024.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko. Kennedy, and What Might Have Been: 'JFK's Last Hundred Days' by Thurston Clarke, page 95 (The New York Times, August 12, 2013)

- ^ "Turner Classic Movies overview". Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Frankenheimer, John, Seven Days in May DVD Commentary, Warner Home Video, May 16, 2000

- ^ a b c Stafford, Jeff, Seven Days in May (article), TCM.

- ^ Frankenheimer, John and Champlin, Charles. John Frankenheimer : A Conversation Riverwood Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-880756-13-3

- ^ Douglas, Kirk. The Ragman's Son. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

- ^ Antulov, Dragan. "All-Reviews.com Movie/Video Review Seven Days In May" (All-Reviews, 2002)

- ^ Pratley, Gerald. The Cinema of John Frankenheimer London: A. Zwemmer, 1969. ISBN 978-0-302-02000-5.

- ^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger (1978). Robert Kennedy and His Times. Futura Publ. ISBN 978-0-7088-1633-2.

- ^ Seven Days in May commentary as part of the Kirk Douglas Featured Collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research Archived June 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Scott Bettencourt, liner notes, soundtrack album, Intrada Special Collection Vol. 235

- ^ Overview, TCM.

- ^ "Seven Days in May". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bamford, James (2001). "Chapter 4: Fists". Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency: From the Cold War Through the Dawn of a New Century. New York: Doubleday. pp. 80–91. ISBN 978-0-385-49907-1. OCLC 44713235. Covers an actual plot during the Kennedy administration and within the Joint Chiefs of Staff to start a war.

External links

[edit]- Seven Days in May at IMDb

- Seven Days in May at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Seven Days in May at the TCM Movie Database

- Seven Days in May at Rotten Tomatoes

- Seven Days in May at TV Guide (revised form of this 1987 write-up was originally published in The Motion Picture Guide)

- 1964 films

- 1960s political thriller films

- American political thriller films

- American black-and-white films

- Bryna Productions films

- Cold War films

- United States presidential succession in fiction

- Films scored by Jerry Goldsmith

- Films about coups d'état

- Films about fictional presidents of the United States

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films directed by John Frankenheimer

- Films produced by Kirk Douglas

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films set in Texas

- Films set in New York (state)

- Films set in 1970

- Films set in the future

- Films about United States Army Special Forces

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by Rod Serling

- Films about World War III

- American neo-noir films

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Films set in Spain

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s American films

- English-language political thriller films